The Passover celebration

Winter holidays get most of the attention, but springtime has major celebrations of note, including Easter and Passover. While most people know what Easter is and when Easter occurs—it’d be hard not to, considering the candy displays in stores—they’re not always aware of the other spring holiday. So what is Passover, exactly?

“Passover is a celebration of one of the core experiences in the history of the Jewish people,” says Rabbi Norman Patz, noting that the holiday commemorates the exodus of the Israelites after 400 years of slavery in Egypt. It’s called Passover because God passed over the houses of the Jews during the 10th and final plague.

That might sound like a pretty intense holiday, but Passover is actually joyous and filled with traditions that are both faith and family based. If you want to learn more about the holiday and its celebration, read on for a Passover primer that’ll help you impress friends and family the next time someone asks, “What is Passover?” or “When is Passover?”

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more holiday tips, fun facts, humor, cleaning, travel and tech advice all week long.

About the experts

|

What is Passover, and why is it important?

Passover, or Pesach as it’s called in Hebrew, is also known as Chag Ha’Aviv, literally “the spring holiday.” Jewish people have celebrated it for thousands of years. It begins on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan, usually in March or April. This year, it runs from April 22 to April 30. It’s celebrated for eight days and nights throughout the world, except in Israel, where it’s a seven-day holiday.

But Passover also brings with it some challenges. “To enjoy the festivities is the easy part,” says Chaplain Mendy Coën, director general of the United States Chaplain Corps. During the holiday, Jewish people are charged with “reflecting inward about the importance of the responsibility of freedom.” This includes and goes beyond commemorating the freedom from thousands of years ago. “It’s critical to realize how grateful we are to live in America,” says Coën, who grew up in Paris, “to be free to act with goodness and kindness.”

For many Jewish families in America, Passover is often a celebration of both our collective past and present.

How is Passover celebrated?

The history of the Jewish people isn’t always a happy one, so when we have a holiday that exists to celebrate our freedom, we really celebrate in style. Families gather together for a great big meal, most often on the first two nights of the holiday. One of the most recognizable elements of Passover is the seder, a ceremonial banquet at which specific foods are eaten (more on those later), prayers are chanted, songs are sung and blessings are made on four glasses of wine.

“Passover includes a ceremonial meal that has specific acts that are connected to the symbolic foods put in the center of the table,” Patz says. Those foods represent elements of the holiday and are placed on a special dish called the seder plate, or K’arah, which sits at the center of the table.

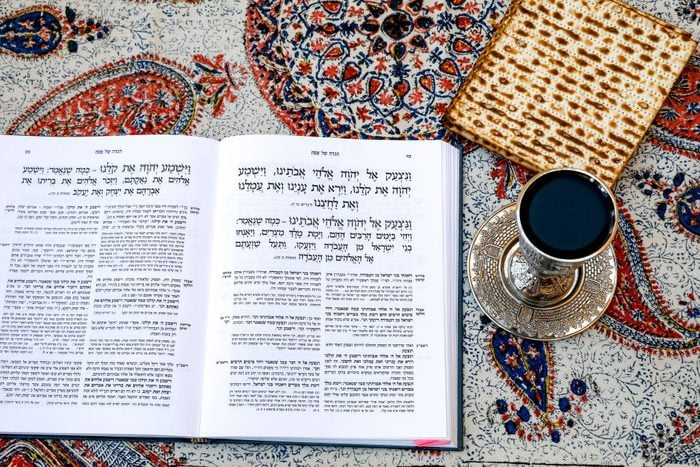

Jewish people gather for two seder meals during Passover. They’re eaten in a specific order and include reading the Haggadah, “the text that tells the story of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt,” says Patz. The Haggadah is most often read in Hebrew or English, with some songs sung in Aramaic or even Ladino, a Judeo-Spanish language formerly spoken by Jews of Spanish (Sephardic) heritage.

The Passover celebration is linked to another springtime observance: Lent. The end of this Christian celebration is the day Jesus celebrated his final Passover.

What do you do during Passover?

Passover prep generally involves a major housecleaning to rid the home of any chametz (leavened food).

The practice of not eating leavened food commemorates the speed with which the ancient Israelites, who were newly freed from slavery, raced to leave Egypt. They were so rushed that they didn’t have enough time for their dough to rise and become bread. Avoiding chametz during Passover is a big deal that’s mentioned in the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. For observant Jews, that means going without bread for the entirety of Passover.

While the majority of Jews follow the guidelines and ritual order listed in the Haggadah, each family has its own traditions and routines. A recurring theme of Passover is May’avdut L’chayrut, which translates to “from slavery to freedom.” This is a notion that resonates deeply with my family.

My late father, David, was a child concentration camp survivor and forced slave laborer to the Nazis during the Holocaust. One of the only familiar perspectives my father could relate to was the American slave experience. And so in my family, in addition to singing all the traditional Passover songs at our seder, we also sang many American slave songs at our Shabbat table each week.

One Passover song, in particular, was sung at the top of our voices at our family seders: “Avadim Hayinu” or We Were Slaves. Singing this with our father allowed us to connect with our immediate family history, the history of slaves in America and our ancient ties to the Jewish slaves in Egypt.

How do you celebrate Passover on a personal level?

Many people use Passover as a time to disconnect from the rest of the world and reset. Some find that this is a great time to reflect on what they want to change in the coming months. “According to Kabbalah, every day has an essence,” says Coën, referencing Jewish mysticism. “We should cherish time. Status quo isn’t something we live in.” That might mean using the week of Passover to set new goals for yourself or determine ways to challenge your own practice or spirituality.

And if that feels too overwhelming, take some time to meditate on your own feelings of freedom. Coën explained that the week of celebrations is akin to a full cycle of living. And during the week (plus a day, if you’re outside of Israel) of Passover, if you’re lucky, you experience “a feeling of gratitude, relaxation and meditation, which connects us to our roots.”

Is Passover meant to be celebrated only with family?

Aside from the Passover seders, the essence of the holiday is celebrating with family or friends. But there aren’t any rules about who you should celebrate with. And because there are two seder nights, you can alternate your celebrations.

On Passover, some families might limit their gathering to their nearest and dearest, while others may have huge open houses with friends and friends of friends. Much in the way that Thanksgiving has led to Friendsgiving, and Valentine’s Day offers an option for Galentine’s Day, there are many ways to celebrate Passover.

The idea of hospitality is actually built into Passover, with part of the liturgy including an announcement beginning with the words Kol Dichfin. That is, “Let all who are hungry come eat.” So go ahead and invite the whole gang for a celebration filled with food, gifts and love.

How long is Passover?

While the Torah states, “Seven days you shall eat unleavened bread” in Exodus 12:15, Diaspora Jews—those living outside of Israel—tend to celebrate an eight-day Passover. The practice has to do with the Jewish calendar, which was based on a lunar cycle.

In ancient times, there was an extensive system of sharing the new month. But getting the word out to people beyond Israel took longer. To ensure holidays were celebrated on the proper dates, an extra day was added to most celebrations outside of Israel. Think of it like covering the bases in case the timing of the holiday was off by a little.

Just as Christian families have their own Easter traditions, each Jewish family has its own way to observe the holiday. Many observant Jews celebrate the first two days and the last two days of the holiday with the greatest stringency. In between, there’s Chol Ha’Moed (meaning “the weekday in the middle of the holiday”), which is usually a time for outings and fun.

Is Passover a kid-friendly holiday?

Yes, children play a big role in the Passover seder and throughout the holiday. For weeks before the holiday, kids might be hard at work on crafts representing the different elements of Passover. You might see different hand puppets, toys or tchotchkes representing the 10 plagues that were said to befall the Egyptians.

Another important tradition is the asking of the Four Questions—in Hebrew, that’s called the mah nishtana. And no, we’re not talking about “What is Passover?” This custom includes asking the most well-known Passover question: “Why is this night different from all other nights?” While the honor of asking the Four Questions usually falls to the youngest person present, that’s more of a tradition than a rule.

As with most Jewish holidays, family tradition is as important as what’s handed down—even for rabbis. Patz says that every year, he chose one of his children to read the Anne Frank story during the Passover seder. And, he says, after visiting the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, they read it with even more emotion.

What are Passover foods?

The Passover seder includes a mix of food—some symbolic and others simply yummy. These are the symbolic foods you’ll find at the seder:

-

Matzo: Also spelled “matzoh” or “matzah,” this unleavened, cracker-like flatbread “represents the speedy exit of the Jews from Egypt,” according to Patz.

-

Greens: The greens on the seder plate represent the hopefulness of springtime. Most people use parsley or similar greens, but some use boiled potatoes.

-

Salt water: This is meant to represent the tears shed by the Jews. At one point during the seder, everyone around the table dips a vegetable into the salt water.

-

Maror: Bitter herbs known as maror represent the bitterness of slavery.

-

Haroseth: Sometimes spelled “haroset,” “charoseth” or “charoset,” this dish is most often made with grated apples, wine or grape juice and grated nuts. It’s meant to resemble the mortar the ancient Israelites used to build cities as slaves in Egypt.

- Hard-boiled egg: Round foods are often eaten symbolically at Jewish festivals because they represent a full life cycle. A hard-boiled egg represents spring and the circle of life, and it’s often compared to the Jewish people: Most foods become softer when they’re cooked, but a hard-boiled egg starts off soft and becomes hard as it cooks. Likewise, no matter the tribulations the Jews have been through over the centuries, they become stronger and tougher under pressure.

-

Roasted shank bone: This represents the first Passover sacrifice.

-

Bitter lettuce: Known as chazeret, some type of lettuce makes its way onto the seder plate, most often romaine.

-

Wine: There are four cups of wine drunk throughout the seder, with a blessing made before and after each one.

What are other Passover foods eaten at the seder?

For many people, the best part of the seder happens after reciting the story of Passover, when you get to Shulchan Aruch, the festive meal. There are many foods eaten on Passover, though each family may pull from its own cultural traditions when deciding what to make. These are some standouts to look forward to at a seder:

- Chicken soup: The soup is often the classic starter for Jewish holiday meals. Some people add matzo balls to their soup (don’t be shy about using a matzo ball mix), though the recipe for matzo ball soup is pretty easy.

- Beef brisket: It’s not required, but it is traditional.

-

Crepes: In my Hungarian/Romanian Jewish family, I’m the official palacsinta (Hungarian crepe) maker and spend hours before the seder whipping up paper-thin crepes to be made into egg noodles or desserts.

-

Macaroons: Unlike trendier French-style macarons, macaroons are soft, coconut-based cookies that come in flavors such as chocolate, chocolate chip, chocolate-dipped, coconut and more. They’re one of those unexplainable things about Passover and tend to show up everywhere.

-

Sweet wine: There’s a misconception that old-school Manischewitz—you know, that thick kosher wine—is the only option. But if you search for kosher wines, you’ll be astounded by the new generation of wineries, vintners and incredible wines.

-

Flourless desserts: Passover is definitely a gluten-free dream. In days gone by, you might have been hard-pressed to find something delicious to end your meal. These days, easily accessible alternative flours, such as almond flour, mean anyone can create exquisite desserts.

-

Afikomen: This dessert may not make you salivate, but it is fun. At the beginning of the seder, a stack of three matzos is placed on the table. During the meal, the middle matzo is broken, and the person leading the seder hides one of the pieces. Later in the evening, the kids search for the hidden half of matzo—known as the afikomen (Greek for “dessert”). Once found, the piece of matzo is divided and shared after the meal, just like a dessert. As part of the tradition, the child who finds the afikomen can ask for a gift of their choice.

What are some ancient and modern Passover traditions?

The seder as we know it today comes from a model of Roman-style banquets, during which people reclined. “Reclining represents freedom and leisure,” says Patz. “The idea is that only free people can sit when they eat. Now, we are free people, so we sit.” At the seder, the person leading the rituals usually leans to the left while seated to mimic the ideals of a free person.

Plenty of traditions from early Passover celebrations have lasted through the ages, but there have been some changes for modern times. Take, for instance, remote get-togethers. If you can’t celebrate with friends or family in person, consider a Zoom seder.

Chef Penny Davidi, who works with chef-made delivery service Hungry, sometimes sends out care packages with everything needed for a Passover seder: the Haggadah, matzo, greens, wine and more. “There are some items that cannot be sent out, like the egg and haroseth,” she says. In those cases, she attaches a “great recipe with a list of items you need to grab from your pantry.”

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions, as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. For this piece, we included expert insight from various sources, including Jewish writer Rachel Weingarten; Rabbi Norman Patz, the rabbi emeritus at Temple Sholom of West Essex; Chaplain Mendy Coën, the director general of the United States Chaplain Corps; and Penny Davidi, a chef with the chef-made delivery service Hungry. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing, and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- Rabbi Norman Patz, rabbi emeritus at Temple Sholom of West Essex in New Jersey

- Chaplain Mendy Coën, director general of the United States Chaplain Corps

- Penny Davidi, chef with Hungry, a chef-made delivery service