Scientists May Have Found the Cause of Alzheimer’s Disease—And How to Reverse It

Updated: May 03, 2021

Good news: Brain experts were wrong about the cause of Alzheimer’s. Better news: Now it should be easier to treat

The tragedy of Alzheimer’s disease begins with the way it robs memory, personality, and lives. Then there’s the condition’s resistance to treatment: 99 percent of the therapies developed by neurologists and pharmaceutical companies have failed, according to a recent study. There may be hope on the horizon, though. Two new areas of research suggest that the disease may be a type of infection—and we may already have a way to treat it.

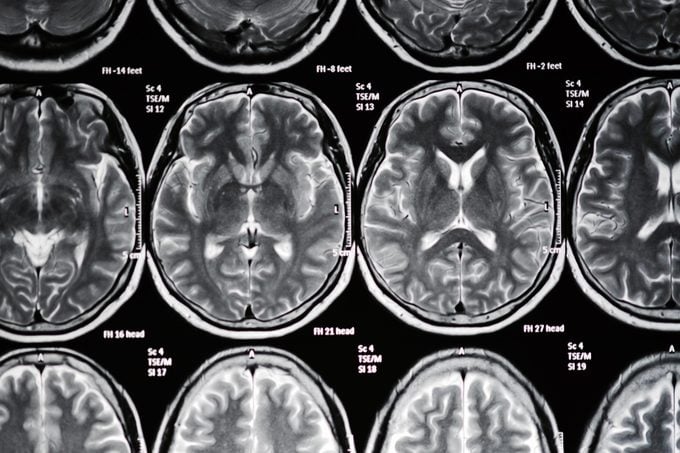

For decades, brain researchers have focused on blocking one of the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s—the buildup of proteins known as amyloid and tau. Scientists have designed many therapies that target the plaques and tangles left by amyloid and tau, but in test after test, patients fail to benefit. Recently, experts have begun to doubt the “amyloid hypothesis” as a cause of Alzheimer’s in part because blocking the proteins doesn’t seem to do any good, but also because many people have amyloid plaques but no symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

A new theory has emerged, and it not only explains why patients can have masses of amyloid and tau proteins in the brain, but also why targeting those proteins won’t help: Welcome to the “infection hypothesis.” Brain scientists have learned that these proteins act as part of the brain’s defense system, trapping infectious invaders like bacteria and viruses. In other words, rather than amyloid and tau being the cause of Alzheimer’s disease, they could be a symptom. If a lot of microbial invaders make it passed the blood-brain barrier and take up residence, the brain could end up with loads of plaque and tangles.

This is where the new studies—and the infectious hypothesis—comes in. A team of researchers led by Jan Potempa, PhD, of the University of Louisville‘s Department of Oral Immunology and Infectious Diseases in the School of Dentistry have found that the bacteria behind chronic gum disease, Porphyromonas gingivalis, can migrate to the brain. Once there, the bacteria releases toxins called gingipains that attack the areas of the brain involved in memory and critical thinking. Some studies have found that living with gingivitis (gum disease) for more than 10 years increases the risk of Alzheimer’s by as much as 70 percent, reports WebMD.

In Potempa’s study, published in the journal Science Advances, the team analyzed the brains of deceased Alzheimer’s patients as well as living ones suspected of having the condition; sure enough, the bacteria was present and seemed to contribute to disease progression. Their findings are the first to establish a link between the P. gingivalis and Alzheimer’s in humans, according to Potempa. It also suggests the “potential for a class of molecule therapies” in the treatment of the disease, though more study needs to be done, he cautions.

There may be more than one type of brain intruder responsible for Alzheimer’s. A review of research published in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience points to evidence dating back to 1991 that herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1—it causes cold sores) can be linked to Alzheimer’s. The trick has been determining whether it’s there by coincidence or if it’s actively damaging the brain—something a study published earlier this year in Neurotherapeutics helped tease out. Taiwanese epidemiologists discovered that people infected with HSV-1 had three times the risk of developing Alzheimer’s later in life compared with those who were virus-free. Even more remarkable, the researchers found that infected patients who had sought antiviral treatment (using drugs like acyclovir) were able to cut their risk of Alzheimer’s by a factor of ten. In a commentary on the study, experts at the universities of Manchester and Edinburgh say that the results raise the possibility that antiviral drugs—and potentially vaccinations—may offer protection against Alzheimer’s. Here are some other diseases some scientists think may be related to Alzheimer’s.

These results are giving researchers the hope that they’re honing in on a potential source—and solution—for Alzheimer’s. The reality is that there may be numerous microbes that can infect the brain: A recent finding published in the journal Neuron indicates a strong connection between Alzheimer’s and the herpes viruses (HSV-6A and HSV-7) responsible for the childhood rash called roseola. Another possible key to the puzzle is that having a genetic susceptibility to Alzheimer’s—a variant of the ApoE gene—seems to leave people more vulnerable to the ravages of these viruses and bacteria.

Last year, the National Institutes of Health spent almost $2 billion on researching the amyloid hypothesis. Recently, the Infectious Diseases Society of America announced $100,000 in grants for researchers exploring the infectious hypothesis, reports NPR. It’s a drop in the bucket by comparison, but new infectious-related studies are already underway, testing antiviral drugs, vaccines, and even medications that can block damaging gingipain toxins. While it might sound bizarre and frightening that you could “catch” Alzheimer’s disease, the infectious hypothesis could become a welcome reality. Make sure you know the 10 early signs of Alzheimer’s.