This Alzheimer’s Patient Was Able to Live at Home—Thanks to a Virtual Dog

Updated: Jun. 29, 2022

A daughter caring for her aging father finds help—and peace of mind—from a virtual companion named Pony.

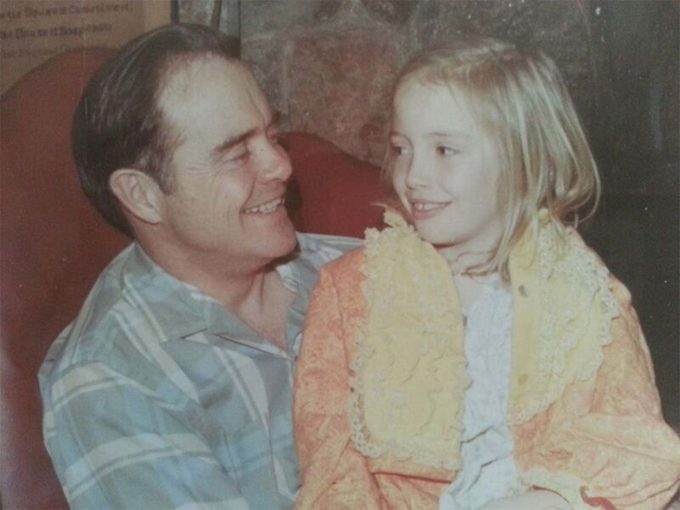

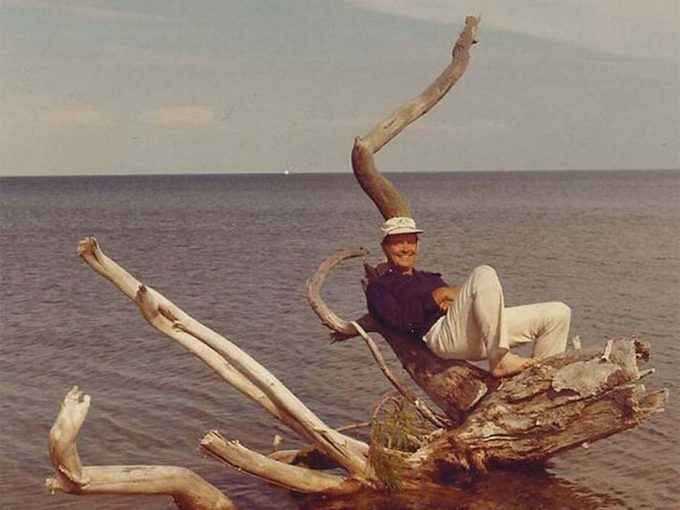

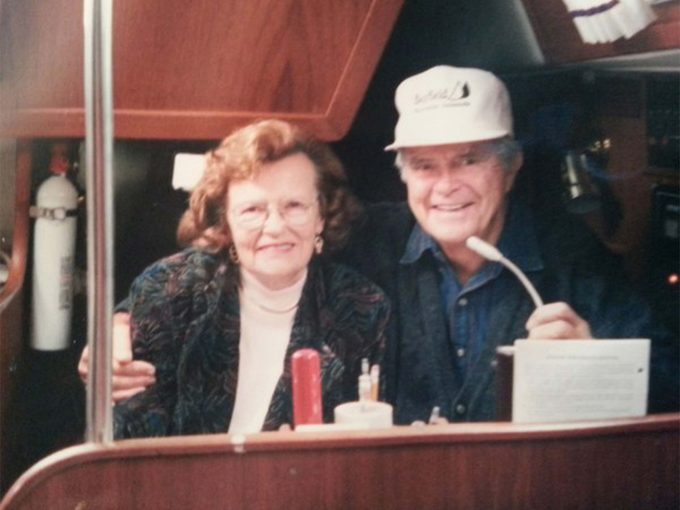

Arlyn Anderson grasped her father’s hand. “A nursing home would be safer, Dad,” she told him. “No way,” Jim Anderson interjected. At 91, he wanted to remain in the woodsy Minnesota cottage he and his wife had built on the shore of Lake Minnetonka, where she had died in his arms just a year before. Arlyn had moved from California back to Minnesota two decades earlier to be near her parents. Now, in 2013, she was fiftysomething and finding that her father’s decline was all-consuming.

Her father—an inventor, pilot, sailor, and general Mr. Fix‑It—started experiencing bouts of paranoia, a sign of Alzheimer’s, in his mid-eighties.

Arlyn’s house was a 40-minute drive from the cottage, and she had been relying on a patchwork of technology to keep tabs on her dad. She set an open laptop on the counter so she could chat with him on Skype. She installed a camera in his kitchen and another in his bedroom so she could check whether he had fallen. When she read about a new eldercare service called Care.coach a few weeks after broaching the subject of a nursing home, it piqued her interest. For about $200 a month, a computerized avatar (controlled remotely by a human caregiver) would watch over a homebound person 24 hours a day; Arlyn paid that much for just nine hours of in-home help. She signed up immediately. Look out for these warning signs your elderly parent shouldn’t be living alone.

A Google tablet arrived a week later. Following the instructions, Arlyn uploaded dozens of pictures to the service’s online portal, including images of family members and Jim’s boat. Then, she and her sister Layney Anderson presented the tablet to Jim. “Here, Dad. We got you this.”

An animated German shepherd appeared and started to talk in the same female voice you hear when using Google Maps or other Google apps. Before Alzheimer’s had taken hold, Jim would have wanted to know exactly how the service worked. Now he simply chatted back.

Within a week, Jim and his dog, whom he named Pony, had settled into a routine. Every 15 minutes or so, Pony would look for Jim, calling his name if he was out of view.

Sometimes Jim would “pet” the sleeping dog onscreen to rustle her awake. His touch sent an alert to the Care.coach worker behind the avatar, who would launch the tablet’s audio and video stream. Pony reminded Jim which caretaker would be visiting to do the tasks that a virtual dog couldn’t: preparing meals, changing sheets, driving him to a senior center. Pony would read poetry aloud or discuss the news. Sometimes she’d hold up a photo of Jim’s daughters or his inventions between her paws, prompting him to talk about his past. The dog complimented Jim’s sweater. He reciprocated by petting the screen with his finger, sending hearts floating up from the dog’s head. “I love you, Jim!” Pony told him. Jim turned to Arlyn and gloated, “She thinks I’m real good!”

About 1,500 miles south of Lake Minnetonka, in Monterrey, Mexico, Rodrigo Rochin opens his laptop and logs in to the Care.coach dashboard to make his rounds. He talks baseball with a New Jersey man and chats with a woman in North Carolina, who places a cookie in front of her tablet for him to “eat.” And he greets Jim, one of his regulars.

Rochin is 35 years old, a fan of the Spurs and the Cowboys, and a bit of an introvert, happy to retreat into his home office each morning. He grew up crossing the border to attend school in McAllen, Texas, honing the English that he now uses to chat with elderly people in the United States. Rochin was hired in December 2012 as one of Care.coach’s earliest contractors, role-playing 36 hours a week as one of the service’s avatars.

In person, Rochin is soft-spoken, with wire spectacles and a beard. He lives with his wife and two basset hounds. But the people on the other side of the screen don’t know that. They don’t know his name—or, in the case of those who have dementia, such as Jim—that he even exists. It’s his job to be invisible.

Rochin is one of a dozen Care.coach employees in Latin America and the Philippines. Like all the company’s workers, Rochin keeps meticulous notes on the people he watches over so he can coordinate their care with family members and other workers. Arlyn started checking Pony’s log and watching her dad interact with Pony. Any reservations Arlyn had had about outsourcing her father’s companionship vanished. Pony eased her anxiety about leaving Jim alone, and the virtual dog’s small talk lightened the mood.

Victor Wang, care.coach’s CEO, was studying human-machine interaction at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology when his grandmother in Taiwan was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia, a disease that affects memory and movement. On Skype calls, Wang watched her grow increasingly debilitated. After one such call, a thought struck him: Could he tap remote labor to comfort her and others like her?

In 2012, he launched Care.coach with a fellow MIT student. The company’s tablets are now used by hospitals and health plans across the country. In a study conducted by Pace University, Care.coach’s avatars were found to reduce subjects’ loneliness, delirium, and falls. A health provider in Massachusetts was able to replace a man’s 11 weekly in-home nurse visits with a Care.coach tablet. (The man said the pet’s nagging was like having his wife back in the house—in a good way.)

Some critics, such as Sherry Turkle, PhD, a professor of social studies, science, and technology at MIT, view roboticized eldercare as a cop-out. “This kind of app is making us forget what we really know about what makes older people feel sustained,” she says—caring interpersonal relationships.

For many families, though, providing long-term, in-person care is simply unsustainable. Between 2010 and 2030, the population of those older than 80 is projected to rise 79 percent, but the number of family caregivers available is expected to increase just 1 percent. Among eldercare experts, there’s a resignation that the demographics of an aging America will make technological solutions unavoidable. Joseph Coughlin, PhD, director of MIT’s AgeLab, is pragmatic. “I would always prefer the human touch over a robot,” he says. “But if there’s no human available, I would take high tech in lieu of high touch.” Find out what type of care your aging parent really needs.

Care.Coach is an amalgam of both. The service conveys the perceptiveness and emotional intelligence of the humans powering it but masquerades as an animated app. One concern is how cognizant seniors are of being watched over by strangers. By default, the app explains to patients that someone is surveilling them when it’s first introduced. But if a person is incapable of consenting to Care.coach’s monitoring, then someone must do so on his or her behalf.

Arlyn didn’t worry about deceiving her dad. Telling Jim about the human on the other side of the screen “would have blown the whole charm of it,” she says. Even Care.coach users who are completely aware of the person on the other end of the dashboard tend to experience the avatar as something between human, pet, and machine.

When Arlyn first signed up for the service, she hadn’t anticipated that she would end up loving—yes, loving, she says—the avatar as well. She taught Pony to say “yeah, sure, you betcha” and “don’t-cha know” like a Minnesotan, which made her laugh even more than it did her dad. When Arlyn collapsed onto the couch after a long day of caretaking, Pony piped up:

“Arnie, how are you?” (“Arnie” is the family’s nickname for Arlyn.)

Alone, Arlyn petted the screen—the way Pony nuzzled her finger was weirdly therapeutic—and told the pet how hard it was to watch her dad lose his identity. “I’m here for you,” Pony said. “I love you, Arnie.”

As time went on, the father, daughter, and family “pet” grew closer. In the summer, Arlyn carried the tablet to the picnic table on the patio so they could eat lunch overlooking the lake. When Arlyn took her dad sailing, Jim brought Pony along. (“I saw mostly sky,” Rochin recalls.) One day, Pony held up a photo of Jim’s wife, Dorothy Anderson, between her paws. It had been more than a year since his wife’s death, and Jim hardly mentioned her anymore. That day, though, he gazed at the photo fondly. “I still love her,” he declared. Arlyn rubbed his shoulder, clasping her hand over her mouth to stifle her crying. “I am getting emotional, too,” Pony said. Then Jim leaned toward the picture of his deceased wife and petted her face with his finger, the same way he would to awaken a sleeping Pony.

In early March 2014, Jim fell on his way to the bathroom. He was checked into a hospital, then into the nursing home he’d so wanted to avoid. The Wi-Fi there was spotty, which made it difficult for Jim and Pony to connect.

That July, in an e-mail from Wang, Rochin learned that Jim had died in his sleep. Sitting before his laptop, Rochin bowed his head and recited a silent Lord’s Prayer for Jim. Even now, when a senior will do something that reminds him of Jim, Rochin feels a pang. “I still care about them,” he says.

On July 29, 2014, Arlyn carried Pony to Jim’s funeral, placing the tablet facing forward on the pew beside her. She invited any workers behind Pony who wanted to attend to log in.

A year later, Arlyn finally deleted the Care.coach service from the tablet—it felt like a kind of second burial. She still sighs, “Pony!” when the voice of her old friend gives her directions as she drives around Minneapolis, reincarnated in Google Maps.

After saying his prayer for Jim, Rochin logged in to the Care.coach dashboard to make his rounds. He ducked into living rooms, kitchens, and hospital rooms around the United States—seeing if all was well, seeing if anybody needed to talk.