Hundreds of American Women Die in Childbirth Every Year—But Why?

Updated: Feb. 22, 2018

The story of one neonatal nurse offers some clues to what’s wrong with our maternity-care system.

Larry Bloomstein’s first inkling that something was seriously wrong with his wife came about 90 minutes after she’d given birth to their daughter on Saturday, October 1, 2011. “I don’t feel good,” Lauren Bloomstein said, pointing to a spot just below her sternum, close to where she’d felt a stabbing sensation during labor.

Larry, an orthopedic trauma surgeon, had been at Lauren’s side much of the last 24 hours, since they had checked into the hospital. Conscious that his role was husband rather than doctor, he had tried not to overstep. Now, though, he pressed the obstetrician-gynecologist, John Vaclavik: What was the matter with his wife?

“He was like, ‘I see this a lot. We do a lot of belly surgery. This is definitely reflux,’” Larry recalls. According to Lauren’s records, Dr. Vaclavik ordered an antacid called Bicitra and an opioid painkiller called Dilaudid. Lauren vomited them up.

Lauren’s pain was soon ten on a scale of ten, she told Larry and the nurses. Ominously, her blood pressure was spiking. An hour after giving birth, the reading was 160/95; an hour after that, 169/108. At her final prenatal appointment, her reading had been just 118/69. Obstetrics wasn’t Larry’s specialty, but he knew enough to ask a nurse: Could this be preeclampsia?

Preeclampsia, or pregnancy-related high blood pressure, can become very dangerous very quickly, leading to seizures and strokes in expectant or new mothers. But in developed countries, it is highly treatable with antihypertensive drugs and magnesium sulfate to prevent seizures. The key is to act fast. By standardizing its approach, Britain has reduced preeclampsia deaths to one in a million—a total of two deaths from 2012 to 2014. In the United States, on the other hand, preeclampsia still accounts for about 8 percent of maternal deaths—50 to 70 women a year. (Here are the preeclampsia symptoms you may not know about.)

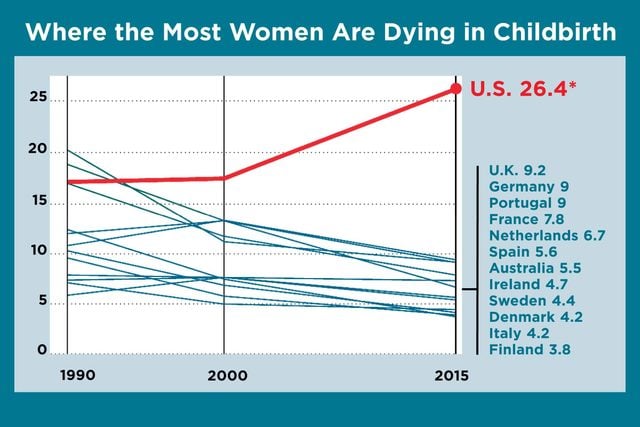

The ability to protect the health of mothers and babies in childbirth is a basic measure of a society’s development. Yet every year in the United States, 700 to 900 women die from pregnancy or childbirth-related causes, and some 65,000 nearly die—the worst record in the developed world. In every other wealthy country, and many less affluent ones, maternal mortality rates have been falling. But in the United States, maternal deaths increased from 2000 to 2014. In a recent analysis by the CDC Foundation, nearly 60 percent were preventable. The fragmented health system makes it hard for new mothers, especially those without good insurance, to get the care they need. Confusion about how to recognize worrisome symptoms and treat obstetric emergencies makes caregivers more prone to error.

Preeclampsia, for example, affects 3 to 5 percent of expectant or new mothers in the United States, up to 200,000 women a year. It can strike out of the blue. But its symptoms—swelling, rapid weight gain, gastric discomfort and vomiting, headache, and anxiety—are often mistaken for the normal irritations that crop up during pregnancy or after giving birth. “We don’t have a yes-no test for it,” says Eleni Tsigas, executive director of the Preeclampsia Foundation.

Yet the lifesaving practices that have become widely accepted in other affluent countries—and in a few states, notably California—have yet to take hold in many American hospitals. Outdated notions—for example, that delivering the baby cures the condition—unfamiliarity with best practices, and lack of crisis preparation can further hinder the response.

“We worry a lot about vulnerable little babies,” says Barbara Levy, vice president for health policy/advocacy at the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and a member of the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. “We don’t pay enough attention to those things that can be catastrophic for women.” (These are common pregnancy myths every mom-to-be can ignore.)

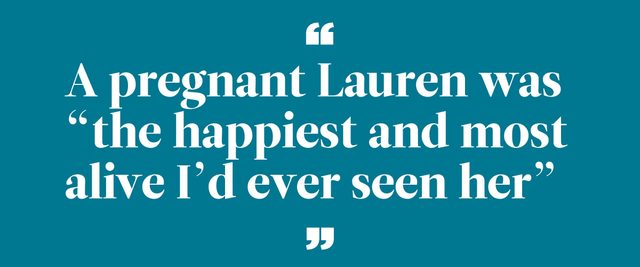

Lauren Bloomstein was maybe the last person you’d expect to find in this kind of catastrophic situation. As a neonatal intensive care nurse, she had been taking care of other people’s babies for years. Finally, at 33, she was thrilled to be expecting one of her own. The prospect of becoming a mother made her giddy—“the happiest and most alive I’d ever seen her,” says Larry. When Lauren was 13, her mother died of a massive heart attack. The chance to create her own family, to be the mother she didn’t have, touched a place deep inside her.

Other than some nausea in her first trimester, the pregnancy had gone smoothly. Larry helped monitor her blood pressure at home, and all was normal. On Lauren’s days off, she got organized, picking out strollers and car seats, stocking up on diapers and onesies. Despite all she knew about what could go wrong, her only real worry was going into labor prematurely. “You have to stay in there at least until 32 weeks,” she would tell her belly. “I see how the babies do before 32. Just don’t come out too soon.”

When she reached 39 weeks and six days—Friday, September 30, 2011—Larry and Lauren drove to Monmouth Medical Center in Long Branch, New Jersey, the hospital where they had met in 2004 and where Lauren had spent virtually her entire career. If anyone would watch out for her and her baby, she figured, it would be the doctors and nurses she worked with.

The neonatal floor was a world unto itself, Lauren Byron, another longtime nurse there, explains: “There’s a lot of stress and pressure, and you are in life-and-death situations. You develop a very close relationship with some people.” The environment tended to attract very strong personalities. Lauren Bloomstein’s nickname in her family football pool was the Feisty One, so she fit right in. “She was one of those people that everyone liked,” Byron says.

Another person everyone liked was John Vaclavik. He was on call that weekend and had agreed to schedule an induction of labor for Lauren and to handle the delivery himself. Inductions often go slowly, and Lauren’s labor stretched well into the next day. At one point, she was overcome by a sudden, sharp pain in her back, but the nurses bumped up her epidural, and the stabbing stopped. On Saturday, October 1, at 6:49 p.m., 23 hours after Lauren had checked into the hospital, Hailey Anne Bloomstein was born, weighing 5 pounds 12 ounces.

Lauren’s blood pressure was high when she entered the hospital—147/99, according to her admissions paperwork. During labor, she had 21 systolic readings at or above 140 and 13 diastolic readings at or above 90. Later, in a deposition, Dr. Vaclavik called her 147/99 reading “elevated” compared with her usual, but not abnormal. He said he would use 180/110 as a cutoff to suspect preeclampsia. He did order a preeclampsia test around 8:40 p.m., but a nurse noted: “No abnormal labs present.” (According to Larry, the results were borderline.) But Lauren continued to complain of unbearable pain. In his deposition, Dr. Vaclavik attributed that to inflammation of the esophagus, which had afflicted her before. Larry began pushing to call in a specialist. Around 10 p.m., the ob-gyn phoned the on-call gastroenterologist, who ordered an X‑ray and more tests, Dilaudid, and antacids. Nothing helped.

The fact that Lauren gave birth over the weekend may have worked against her. Hospitals may be staffed differently on weekends, adding to the challenges of managing a crisis. A Baylor College of Medicine analysis of 45 million pregnancies in the United States from 2004 to 2014 found that mothers who deliver on a Saturday or Sunday have nearly 50 percent higher mortality rates, as well as more blood transfusions and more perineal tearing. The “weekend effect” has also been associated with higher fatality rates from heart attacks, strokes, and head trauma.

Desperate, Larry reached out to his colleagues in the trauma unit at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, New Jersey. By chance, the doctor on call happened to be a fairly new mother. As Larry described Lauren’s symptoms, she interrupted him. “I know what this is.” She said Lauren had HELLP syndrome, the most severe variation of preeclampsia, characterized by hemolysis, or the breakdown of red blood cells; elevated liver enzymes; and low platelet count, a clotting deficiency that can lead to excessive bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke. “Your wife’s in a lot of danger,” the trauma doctor said.

Larry went to Lauren’s caregivers. They insisted the tests didn’t show preeclampsia, he says. Meanwhile, Lauren’s agony had become almost unendurable. The blood pressure cuff on her arm was adding to her discomfort, so around 10:30 p.m., her nurse removed it—on the theory that, Larry says, “we know her blood pressure is high. There’s no point to retaking it.” According to Lauren’s records, her blood pressure went unmonitored for another hour and 44 minutes. Dr. Vaclavik later acknowledged that, in retrospect, it might have been measured more closely.

Just after midnight, as her blood pressure peaked at 197/117, Lauren complained of a headache. As Larry studied his wife’s face, he realized something had changed: “She suddenly looks really calm and comfortable, like she’s trying to go to sleep.” She gave Larry a little smile, but only the right side of her mouth moved. “She looked at me and said, ‘I’m afraid’ and ‘I love you,’” Larry recalls. “And I’m pretty sure in that moment she put the pieces together. That she had a conscious awareness of … that she was not going to make it.”

Around 2 a.m., a neurosurgeon confirmed what the trauma doctor had said four hours before: Lauren had HELLP syndrome. Then he delivered more bad news: Her blood platelets—essential to prevent hemorrhaging—were dangerously low, and she would need surgery. But, according to Larry, the hospital didn’t have sufficient platelets on-site, so her surgery would have to be delayed. Hours passed before the needed platelets arrived.

Just after noon, the neurosurgeon emerged and said that Lauren was on life support, with no chance of recovery.

All this time, Hailey had been in the nursery, tended by Lauren’s stunned colleagues. They took her to Lauren’s room, and Larry placed her gently into her mother’s arms. After a few minutes, the nurses whisked her back up to the third floor to protect her from germs. A respiratory therapist removed the breathing tube from Lauren’s mouth. At 3:08 p.m., surrounded by loved ones, she died.

After that day, people asked Larry a lot of questions. Everyone wanted to know how this could have happened. Despite the missteps he had witnessed, Larry was hesitant to lay blame. But the fact that someone with Lauren’s advantages could die so needlessly was symptomatic of a bigger problem. By some measures, New Jersey had one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the United States. He wanted authorities to get to the root of it—to push the people and institutions that were at fault to change.

That’s the approach in the United Kingdom, where maternal deaths are regarded as systems failures and investigated by a national committee of experts. Its reports help set policy for hospitals throughout the country. In the United States, maternal mortality reviews are left up to states. As of last spring, 26 states (and one city, Philadelphia) had a well-established process in place; another five states had committees that were less than a year old. In almost every case, resources are tight, the reviews take years, and the findings get little attention. New Jersey’s review committee doesn’t interview the relatives of the deceased, nor does it assess whether a death was preventable. A bipartisan bill in Congress, the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2017, would authorize funding for states to establish review panels or improve their processes. It went to the Congressional Subcommittee on Health in March 2017.

Someone eventually steered Larry toward the New Jersey Department of Health’s (DOH) licensing and inspection division, which oversees hospital and nursing home safety. He filed a complaint against Monmouth Medical Center. In December 2012, the DOH issued a report backing up everything Larry had seen firsthand. The report faulted the hospital. As a result, Monmouth established mandatory education about preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome and more training on life support and communications. Some of the changes were strikingly basic: Staff nurses were urged to obtain patients’ prenatal records and to check vital signs regularly.

Larry was gratified by the findings but dismayed that they weren’t publicly posted. That meant hardly anyone would see them. The DOH forwarded his complaint to the Board of Medical Examiners and the New Jersey Board of Nursing. After a full inquiry, the Board of Medical Examiners notified Larry that it had found no basis to discipline Dr. Vaclavik. Nor has the Board of Nursing taken any disciplinary action.

A few months after the DOH weighed in, Larry sued Monmouth, Dr. Vaclavik, and five nurses in Monmouth County Superior Court. For a medical malpractice lawsuit to go forward in New Jersey, an expert must certify that it has merit. Larry’s passed muster. But beyond the taking of depositions, at this point, there has been little action in the case.

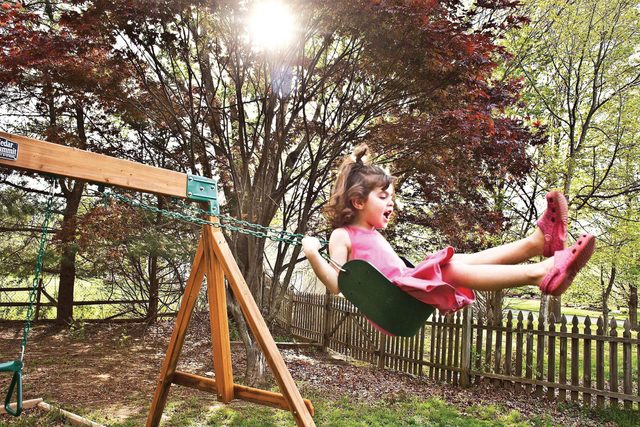

Now six years old, Hailey feels her mother’s presence everywhere, thanks to Larry and his new wife, Carolyn. They met when she was a surgical tech at one of the hospitals he worked at after Lauren died, and married in 2014. Photos and drawings of Lauren occupy their mantel, the bookcase in the dining room, and the walls of the upstairs hallway. Larry’s younger daughter, three-year-old Aria, calls her Mommy Lauren. On birthdays and holidays, Larry takes the girls to the cemetery. He designed the gravestone: his handprint and Lauren’s reaching away from each other, Hailey’s linking them forever.